In this study, published in npj Digital Medicine, I apply an unsupervised learning technique known as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to identify condition clusters across millions of patients in the N3C database. Such clusters are not guaranteed to be related to COVID-19, however. To identify those that are, we look at how patients are assigned to clusters before and after COVID-19 infection, integrating the probabilistic nature of LDA and supervised models (repeated-measures logistic regression) to predict how patients will migrate toward or away from a cluster post-infection, moderated by demographic factors such as age, sex, and wave of infection.

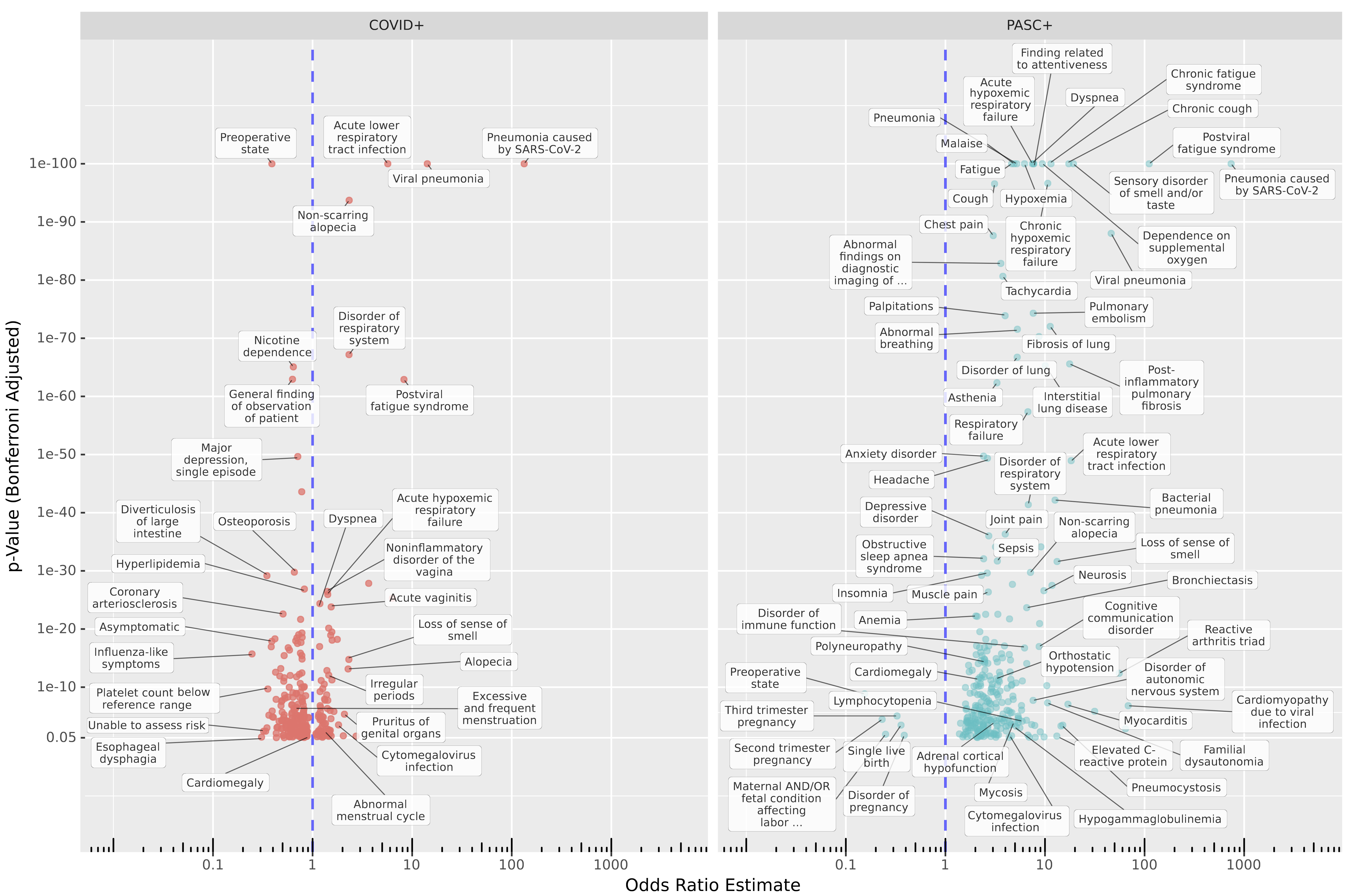

A primary goal here was to apply a data-first approach to identifying Long COVID. As of October 2021 there is an ICD-10 diagnosis code for Long COVID, U09.9. However, it is now generally understood that Long COVID (also known as PASC, for Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection) is a complex set of conditions with varying presentations. Might our shifting understanding of this disease be causing us to miss important sub-types? To check, we looked for conditions increased in patients with Long-COVID diagnoses compared to COVID-naïve Control patients over a similar time frame, and in patients with COVID-19 but no Long-COVID diagnosis compared to Controls. (Please see the preprint for details.)

Some of my favorite features of this work are provided by the flexibility gained from patient/cluster assignment provided by the LDA model, typically used to identify word clusters (called topics) in collections of documents like journal articles or web pages. LDA assigns each patient (in this case) a probability distribution over clusters, where each cluster is a probability distribution over conditions. We can do this for patient records over defined periods of time as well, allowing a creative methodological innovation of treating each patient/cluster assignment as a binomial trial, which we model by repeated-measures logistic regression. This allows us to see how cluster assignment is influenced by factors such as patient demographics, COVID infection status, and Long-COVID diagnosis.

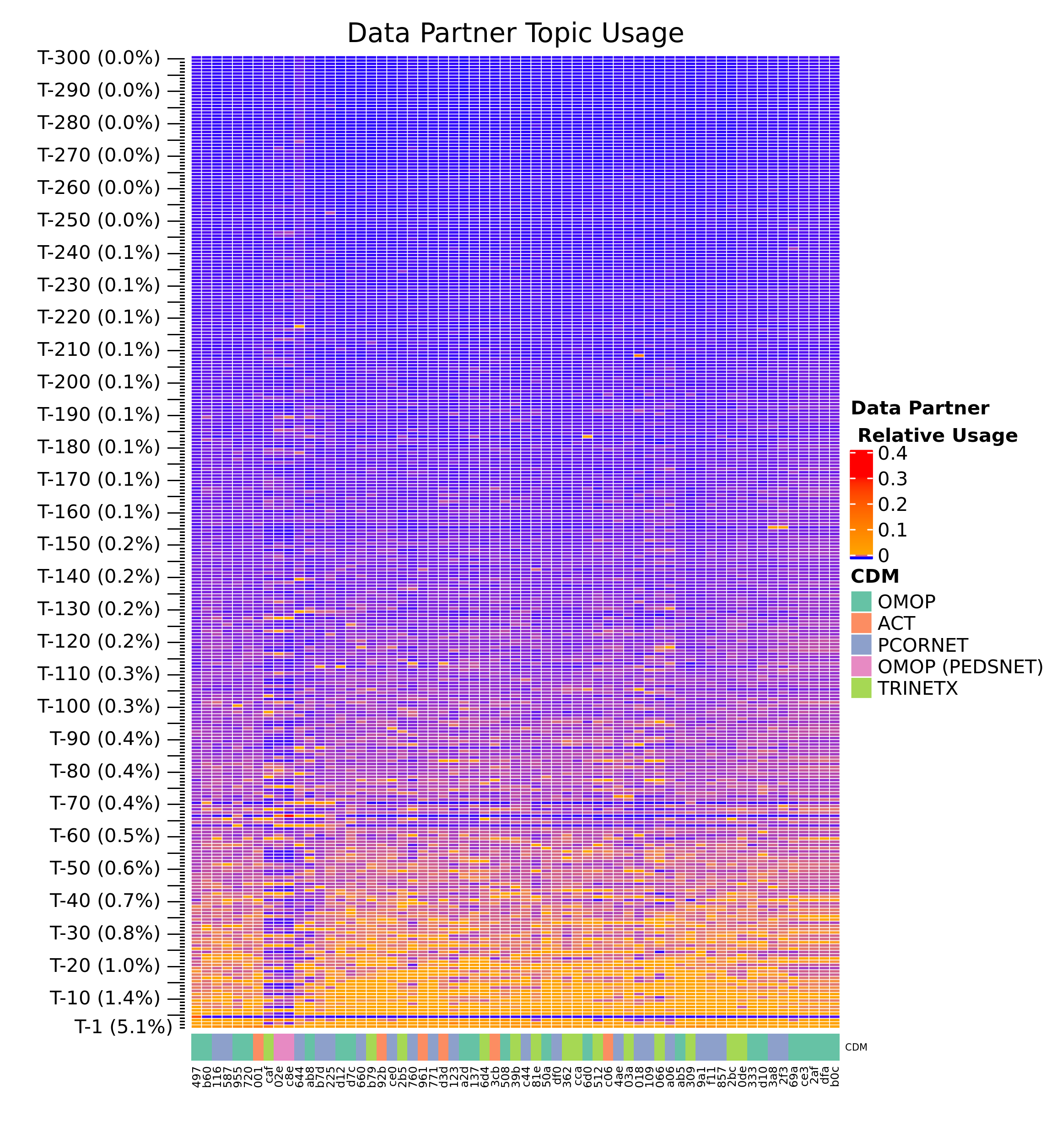

Beyond modeling, we can see how patient/cluster assignment trends across other factors, like which site patient data are drawn from. The figure below illustrates that some clusters are not used uniformly by various healthcare organizations. Although we do not know which specific organization each patient comes from (for patient privacy), we do have hints, for example OMOP (PEDSNET) sites in the figure below display distinct trends in cluster usage relating to their pediatric focus.

Finally, it is worth noting the value of large datasets in unsupervised learning. While most applications of LDA to structured health data to date have found anywhere from 6 to 60 coherent clusters, our modeling of millions of patients and hundreds of millions condition records reveals hundreds of clinically-relevant clusters, including rare diseases and their corresponding symptoms.